The Maltese connection with Iran sanctions busting

![]()

An investigative reporter’s killing has shone new light on a shadowy deal she uncovered

Cynthia O’Murchu in London – April 5, 2018

The day after a car bomb claimed the life of Maltese investigative reporter Daphne Caruana Galizia, in October last year, one of the 47 libel suits against her was quietly dropped at a county court in the US.

Maltese private bank Pilatus Bank and its owner, Iran-born Seyed Ali Sadr Hasheminejad, known as Ali Sadr, had filed proceedings against Caruana Galizia earlier last year. The suit came after a series of stories published on her website that claimed Pilatus had laundered funds from allegedly corrupt schemes on behalf of offshore companies and individuals, including Keith Schembri, chief of staff to the Maltese prime minister, Joseph Muscat.

Based in part on the release of files in the Panama Papers, the stories culminated in the claim that Michelle Muscat, the prime minister’s wife, had received $1m from the daughter of President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan, with the money moving through a Panamanian shell company in transactions facilitated by Pilatus.

Mr. Muscat was quick to react, calling the accusations “the greatest lie in Malta’s political history”. Pilatus also responded emphatically. “Pilatus Bank was not set up to criminally launder money. . . Pilatus Bank has not committed any criminal acts. Mr. Sadr has not committed any criminal acts”, the now withdrawn lawsuit filed in May last year says.

The story did not end there. In March, Mr. Sadr was arrested in the US and charged on six counts of evading Washington’s sanctions against Iran. Prosecutors claim he organized a scheme, lasting from 2006 to 2014, to illicitly funnel more than $115m from a Venezuelan housing project to Iranian-controlled companies via western banks.

Prosecutors allege Mr. Sadr used “deceptive means” to hide the role of Iranian parties in the US dollar payments. They say that with the help of seven co-conspirators Mr. Sadr set up Swiss, Turkish and offshore entities and arranged for funds to be transferred through Swiss and US banks. Mr. Sadr had also used a St Kitts and Nevis passport and an address in Dubai, which prosecutors say were intended to mask his Iranian connections.

Following his arrest, Mr. Sadr was removed from his role at Pilatus and his voting rights suspended. The Maltese Financial Services Authority hired an experienced former US regulator to take control of the bank’s assets and stopped all transactions, including withdrawals or deposits. Protesters placed a washing machine and pegged fake euro notes on a washing line outside the bank’s headquarters.

Mr. Sadr last week pleaded not guilty and was denied bail. “Mr. Sadr intends to vigorously defend himself and looks forward to doing so in court,” Baruch Weiss, his lawyer in the sanctions matter, told the Financial Times.

Mr. Sadr’s indictment casts rare light on alleged elaborate schemes that have been created by Iranian entities to evade sanctions. It follows the conviction in January of a Turkish banker in a US sanctions case involving fraudulent billion-dollar gold-for-food transactions.

But it also raises uncomfortable questions for Europe. Amid a procession of scandals that have involved banks in Latvia and Cyprus, the arrest of Mr. Sadr is the latest in a series of cases in which the ability of European regulators, law enforcement agencies and financial institutions to police money laundering has been called into doubt.

Pilatus is not mentioned in the indictment, which was unsealed on March 20, and there is no allegation that the bank was involved in the illicit scheme that led to his arrest. However, the indictment revealed that during the time Mr. Sadr began the process of applying for and obtaining Pilatus’s banking license in Malta, he was still involved in the alleged sanctions evasion scheme and was already under investigation by US authorities. The FT has discovered that in addition to Mr. Sadr, another non-executive director of Pilatus Bank, Mustafa Cetinel, was also investigated in the same probe, although he has not been charged.

In recent months, EU lawmakers, prompted by damning intelligence reports from Malta’s anti-money laundering unit, which were leaked to the media, have repeatedly called for an inquiry into Pilatus Bank. The reports found “major” shortcomings in the bank’s anti-money laundering processes and one, from 2016, referred to intelligence that Mr. Sadr was being investigated in a foreign jurisdiction for money laundering.

Some of the MEPs have echoed questions raised by Caruana Galizia: how could a then 32-year-old with no public record in banking manage to set up a private Malta bank geared to high net worth individuals and politically connected clients? The bank holds more than €300m in assets, according to its latest annual report.

And how was that bank able to open a branch office in London at a time when its owner and chairman and a least one other board member were being investigated by US authorities for their alleged involvement in evading US sanctions and money laundering?

For Maltese MEP David Casa, who has campaigned for Pilatus to be investigated, the problem goes beyond Mr. Sadr’s alleged subterfuge. It exposes, he says, the inherent weakness of the EU’s “passporting” system, which allows financial companies and banks licensed in one country to transfer their permissions to operate in another EU country.

“The proper functioning of the passporting system is necessarily dependent on the robustness of the procedures carried out by the regulatory authority of the member state in which the entity is licensed,” Mr. Casa wrote in a letter to the UK’s Prudential Regulation Authority last month, claiming that regulatory oversight had been compromised in the case of Pilatus.

Danièle Nouy, chairwoman of the European Central Bank supervisory board, told an EU parliamentary committee last month that it was “very embarrassing to depend on the US to do the job”. The ECB does not have a mandate to supervise financial institutions and banks on their compliance with anti-money laundering laws because that role is carried out by local regulators.

Meanwhile, the European Banking Authority is undertaking a preliminary inquiry into the Maltese regulator and the country’s anti-money laundering unit. This followed a letter from 22 MEPs to the EBA’s chairman that blamed “regulatory capture” for “the apparent impunity” with which Pilatus allegedly continued to operate.

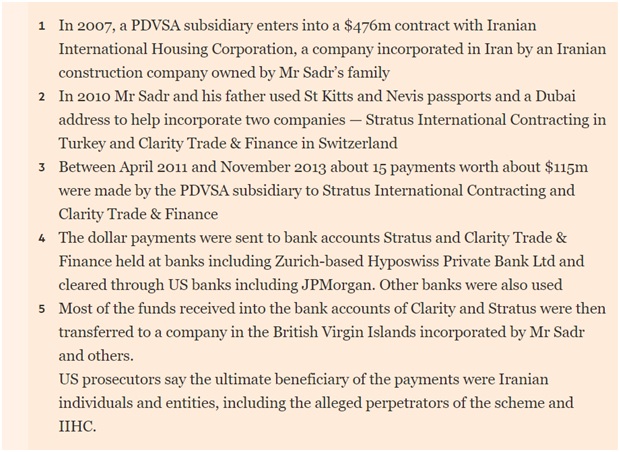

According to the US indictment, the company at the centre of the plan to evade sanctions was Iranian International Housing Corporation, a construction firm incorporated in Tehran by the Sadr family’s main holding company, Stratus Group. In 2007, IIHC entered into a $476m contract with a subsidiary of state-owned Venezuelan oil company PDVSA to build thousands of housing units in the Latin American country.

In order to obscure the involvement of Iranian companies in the deal, prosecutors allege, Mr. Sadr set up a network of front companies and bank accounts. He was able to do this in part because he took advantage of a passport-for-investment scheme from St Kitts and Nevis — a popular scheme among wealthy Iranians who want visa-free travel in much of the world.

In 2014 the US Treasury issued a notice warning that “illicit actors” were using the St Kitts citizenship-by-investment scheme to mask their identity and evade sanctions.

Mr. Sadr was one of the founders of a company in Switzerland called Clarity Trade & Finance and another in Turkey called Stratus International Contracting. The indictment says that between 2011 and 2013, he organized 15 separate payments to IIHC worth $115m that went through these two companies. Most of the funds were eventually transferred to a British Virgin Islands entity that Mr. Sadr and others had incorporated.

US prosecutors have for years been investigating allegedly illicit flows from Venezuela to Iran — part of a broader push by Washington, especially before the 2015 nuclear deal with Tehran, to put pressure on the Iranian economy.

The economic ties between Venezuela and Iran flourished after the election of Mahmoud Ahmedinejad in 2005, as the new president bonded with then Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez in mutual antipathy towards the US. Tehran’s search for new economic partners gained added urgency after the imposition in 2010 of US banking sanctions that crippled its ability to do business within the global financial system.

Documents and emails from the companies indicate the efforts to get around sanctions, US prosecutors say. In a letter dated July 22 2011, seen by the FT and referred to in the indictment, an IIHC director asked for payments to be made through a bank account at Zurich-based Hyposwiss Private Bank Ltd held in the name of a Clarity Trade & Finance. JPMorgan’s New York branch is listed as the intermediary bank. The letter was addressed to Dulcosa, the PDVSA subsidiary that oversaw the government-financed housing project. The funds should go to Clarity Trade & Finance, the director wrote, “in view of the current difficulties for transfer and movement of funds”.

A banker familiar with the transactions who dealt with Mr. Sadr told the FT the bank’s impression was that the business was conducted between a Turkish company and Venezuela. He said there was no indication that the end beneficiary was an Iranian company. “All the contracts were done by lawyers, properly done, and all the shareholders were outside of Iran,” he said.

Like others in the legal and banking sector who worked with Mr. Sadr, he dismissed the sanctions evasion allegations as “politically motivated”.

Mr. Sadr’s father, Mohammed Seyed Hasheminejad, who is an unnamed co-conspirator in the indictment, told the FT that Stratus Group was only a minor shareholder in IIHC. “IIHC has transferred no single penny to Iran and hence has not violated any US sanctions,” he said, denying that the Turkish company was set up to circumvent sanctions.

The contract in Venezuela was to build Ciudad Fabricio Ojeda, a vast housing project in Zulia state. About a third of these apartments remain unfinished, some languishing without basic facilities and vandalised with graffiti, according to a 2017 report by Venezuela’s lobbying group, Transparencia.

The new strategies developed by Iran included bartering oil for other commodities, with payments made via third parties and shell companies in jurisdictions around the world. It also provided opportunities for enterprising individuals to make money.

Mr. Sadr’s father — who is a former chairman of EN Bank, Iran’s first private bank — said 4,000 of the 7,000 housing units had been delivered. “The Venezuelan government has not had money to pay us back,” he said.

Though the indictment does not name him, the FT has established that another of the suspected co-conspirators is Mr. Cetinel, a non-executive director of Pilatus Bank.

According to Turkish public records, Mr. Cetinel held a 4 per cent stake in Stratus International Contracting, the company established by Mr. Sadr to which the allegedly illicit payments were made. One of Mr. Cetinel’s social media profiles shows him in December 2013 attending the opening ceremony of the Ciudad Ojeda housing project.

Prosecutors allege that Mr. Cetinel recommended a name change for IIHC to one that would remove the reference to Iran. Alternative names suggested included “International Iron Housing Company”. Mr. Cetinel did not respond to a request for comment.

According to the US indictment, it seems as though Mr. Sadr was living a double life. At the same time as he was allegedly orchestrating the financial links between Iran and Venezuela, he also set about establishing a bank in Malta.

Mr. Sadr first began applying for a banking license in the summer of 2012. KPMG assisted and advised Mr. Sadr in compiling the application and liaising with the Maltese regulator, according to a letter that Pilatus Bank chief executive Hamidreza Ghanbari sent in January to MEPs. Mr. Sadr’s “source of wealth and source of funds were vetted acutely as part of the MFSA due diligence process”, he wrote.

KPMG declined to comment, citing client confidentiality. Pilatus Bank did not respond to multiple requests for comment. JPMorgan declined to comment, as did St Galler Kantonalbank, which owned Hyposwiss Private Bank Ltd at the time of the transactions.

Little is known about the operations or finances of the companies Mr. Sadr owned. Public records indicate that Clarity Trade & Finance, which claimed to be trading in agricultural commodities, made a profit of €1.2m in 2012, while Stratus International Contracting made nearly €16m in profit.

Mr. Sadr was also a director of Pilatus Capital, a company originally incorporated in the UK as Sirius Trade and Finance by Mehdi Shams, a former employee of the Iranian shipping line Irisl. Mr. Shams was sentenced to death two years ago in Iran for embezzlement.

In early 2017 Pilatus established offices in London’s Mayfair, which Mr. Sadr and Mr. Ghanbari visited regularly. The Financial Conduct Authority, the UK regulator, confirmed that Pilatus Bank had passported its banking licence to the UK but said the bank had not yet opened for business in the UK, meaning it could not carry out regulated activities such as opening accounts.

The MFSA has faced heavy criticism in recent months that it rubber-stamped Pilatus’s licensing application, an accusation that has been rejected by the MFSA as well as Pilatus Bank. The MFSA said it had been closely reviewing and monitoring the bank in line with its supervisory responsibilities and continued to co-ordinate closely with international regulators and law enforcement.

The Maltese authorities have not been helped by information about Mr. Sadr’s political connections. Last month, Maltese media reported that Mr. Muscat and his chief of staff attended Mr. Sadr’s wedding in 2015.

After receiving the preliminary report into the bank’s processes by Malta’s anti-money laundering agency, which Caruana Galizia published on her website, Pilatus engaged the bank’s auditor, KPMG, and a local law firm to conduct a review of the bank’s clients and procedures. That review gave Pilatus a clean bill of health.

The agency subsequently decided its concerns no longer existed. However, after the renewed scrutiny of Pilatus that has followed the US indictment of Mr. Sadr, the Maltese authorities are now being forced to explain why they did not ask more questions about the bank.

Additional reporting by Najmeh Bozorgmehr in Tehran

https://www.ft.com/content/14f961b6-3281-11e8-b5bf-23cb17fd1498